Highlights

- Multiple studies found decreased plasma serotonin levels in patients with long COVID compared to recovered individuals and healthy controls

- Serotonin levels negatively correlated with number of persistent symptoms 3-4 months after acute infection

- Serotonin reduction was observed in both acute COVID-19 and long COVID patients

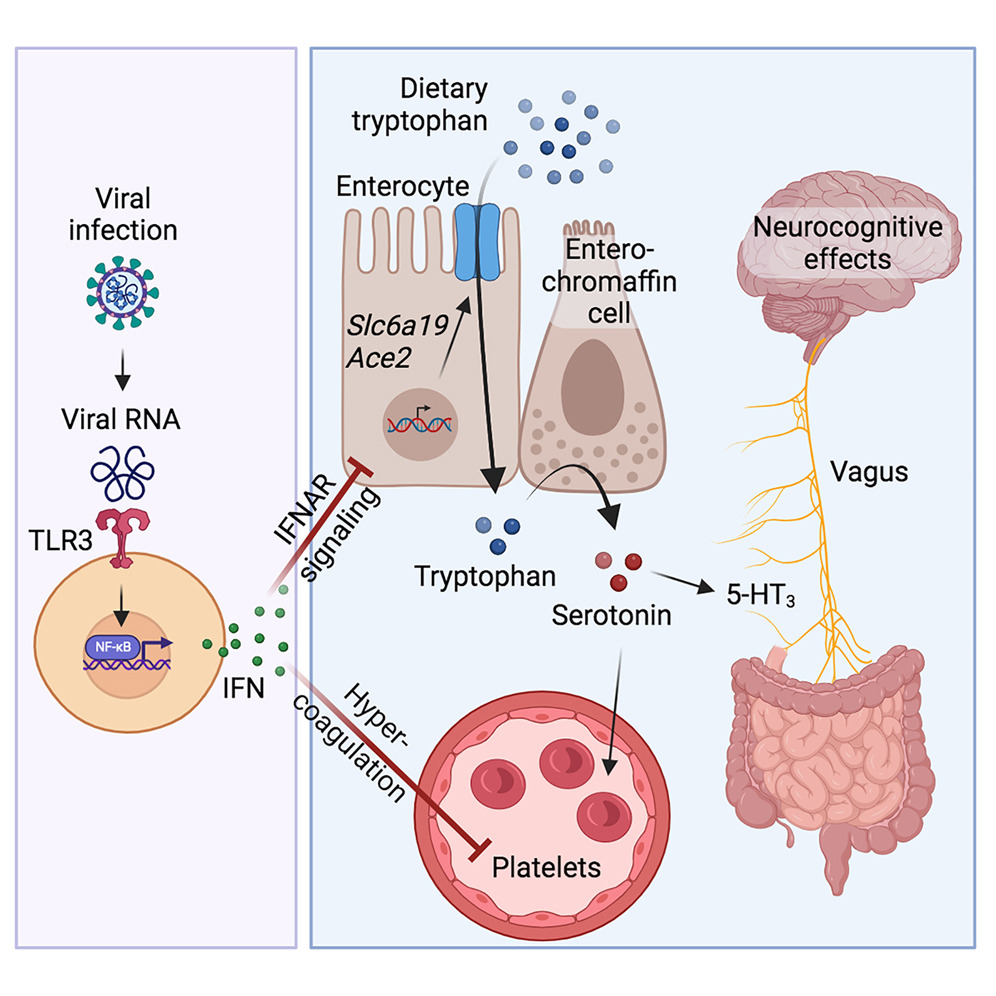

- Serotonin depletion is driven by viral RNA-induced type I interferons (IFNs)

- IFNs reduce serotonin through diminished tryptophan uptake and hypercoagulability

- Peripheral serotonin deficiency impairs cognition via reduced vagal signaling

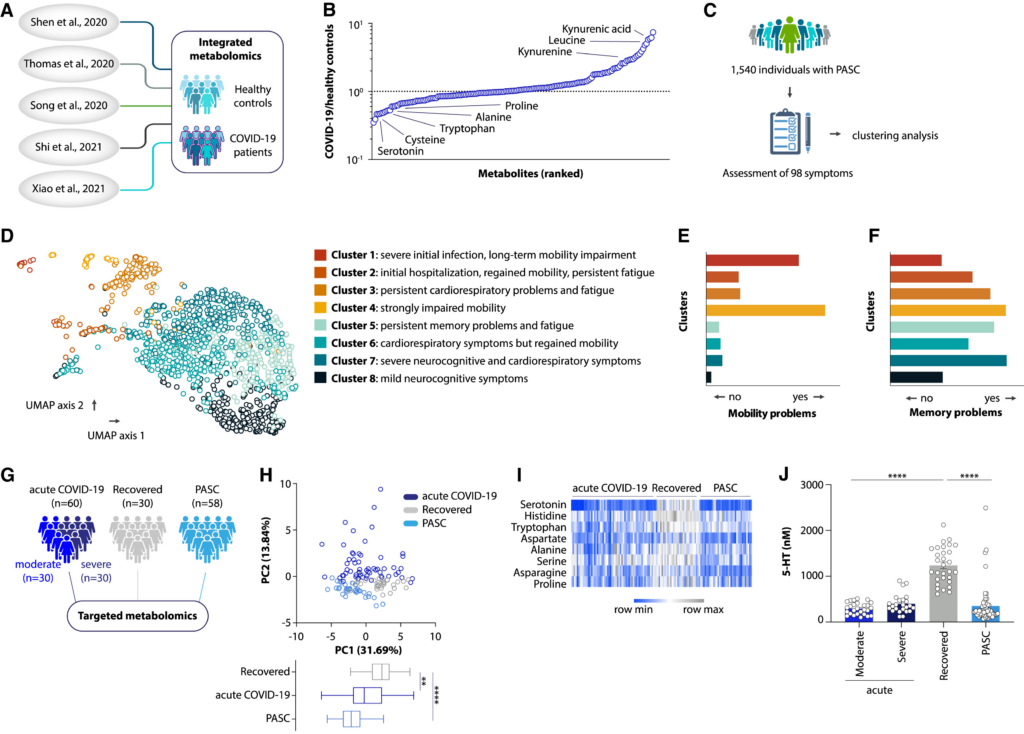

Several interesting aspects to the above diagram:

- Metabolite changes in COVID-19 (Panel B): The graph shows that certain metabolites like kynurenic acid, leucine, and kynurenine are significantly elevated in COVID-19 patients. These levels are higher compared to healthy controls. In contrast, others like serotonin and cysteine are depleted.

- Clustering of PASC symptoms (Panel D): The UMAP plot reveals 8 distinct clusters of long COVID (PASC) patients based on their symptom profiles. This suggests different subtypes of the condition.

- Symptom distribution across clusters (Panels E and F): These show how mobility and memory problems vary across the different PASC clusters, highlighting the heterogeneity of long COVID manifestations.

- Metabolomic differences (Panel H): The PCA plot demonstrates clear metabolic distinctions between acute COVID-19, recovered, and PASC patients.

- Heatmap of metabolites (Panel I): This visualizes how levels of various metabolites, including serotonin, differ across the three patient groups.

- Serotonin levels (Panel J): This graph clearly shows that serotonin levels are significantly reduced in both acute COVID-19 and PASC patients compared to recovered individuals, with PASC patients having the lowest levels.

The most striking finding is the persistent depletion of serotonin in PASC patients. This condition persists even after recovery from acute infection. This depletion could explain some of the long-term symptoms experienced by these individuals.

Mechanisms of Serotonin Depletion:

Reduced intestinal tryptophan uptake:

- Viral inflammation downregulates expression of amino acid transporters (e.g. ACE2, SLC6A19) in intestinal cells

- This impairs absorption of tryptophan, the precursor for serotonin synthesis

Thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction:

- Viral infection causes platelet hyperactivation, aggregation and depletion

- Platelets are the major reservoir of circulating serotonin, so their loss reduces serotonin storage capacity

Enhanced serotonin turnover:

- Increased expression of monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes that break down serotonin

- Higher levels of serotonin metabolites (e.g. 5-HIAA) found in urine

Persistent viral reservoirs:

- Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in gastrointestinal tract long after acute infection

- Ongoing inflammation from viral persistence may drive continued serotonin depletion

Ineffective Treatments:

- Inhibiting kynurenine production (via IDO1 or TDO2) did not restore serotonin levels

- Standard tryptophan supplementation was ineffective due to impaired intestinal uptake

Promising Treatment Approaches:

Glycine-tryptophan dipeptide supplementation:

- Bypasses impaired amino acid transporters

- Increased both tryptophan and serotonin levels in animal models

5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) supplementation:

- Direct precursor to serotonin, bypassing tryptophan requirement

- Rescued serotonin levels in animal studies

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs):

- Fluoxetine restored cognitive function in animal models

- May help preserve available serotonin

MAO inhibitors:

- Prevented accumulation of serotonin metabolites

- Restored serotonin levels in treated animals

Targeting vagus nerve function:

- Vagus nerve stimulation or 5-HT3 receptor agonists improved cognition

- May help compensate for reduced peripheral serotonin signaling

In conclusion, the research suggests multiple mechanisms contribute to serotonin depletion in long COVID. Treatments aimed at boosting serotonin precursors, preserving existing serotonin, or enhancing downstream signaling show promise for alleviating symptoms.

Here’s a table comparing the various treatment approaches for addressing serotonin deficiency in long COVID:

| Treatment Approach | Mechanism | Efficacy in Studies | Availability | Safety Profile | Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine-tryptophan dipeptide | Bypasses impaired intestinal amino acid transporters | Effective in animal models | Limited; not widely available | Generally considered safe, but limited long-term human data | Oral |

| 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) | Direct serotonin precursor | Rescued serotonin levels in animal studies | Widely available as a supplement | Generally safe, some risk of side effects | Oral |

| MAO inhibitors | Prevent serotonin breakdown | Restored serotonin levels in animals | Available as prescription medications | Can have significant side effects and interactions | Oral |

| SSRIs | Increase available serotonin | Improved cognition in animal models | Widely available as prescription medications | Well-established safety profile, but some side effects | Oral |

| Vagus nerve stimulation | Compensates for reduced peripheral serotonin signaling | Improved cognition in animal models | Limited; typically requires medical device | Generally safe, but invasive | Device implantation or external stimulator |

| 5-HT3 receptor agonists | Enhances serotonin signaling | Improved cognition in animal models | Limited availability; some are prescription drugs | Varies by specific drug, can have side effects | Typically oral |

| Standard tryptophan supplementation | Increase serotonin precursor | Ineffective due to impaired uptake | Widely available as a supplement | Generally safe, but can interact with some medications | Oral |

| Kynurenine production inhibitors | Theoretically increase tryptophan availability for serotonin | Not effective in studies | Not widely available | Limited data on safety | Varies |

Glycine-tryptophan dipeptide supplementation

One of the most promising treatments was glycine-tryptophan dipeptide supplementation. Unfortunately, glycine-tryptophan dipeptide is not widely available as a standard supplement for patients. Here’s some key information about its availability and status:

- Research status: The use of glycine-tryptophan dipeptide for treating serotonin deficiency in long COVID is still in the experimental stage. The studies mentioned in the image primarily used animal models.

- Not FDA-approved: There is currently no FDA-approved glycine-tryptophan dipeptide supplement specifically for treating long COVID or serotonin deficiency.

- Limited commercial availability: Some specialty supplement companies may offer glycine-tryptophan dipeptides, but these are not regulated as medications and their quality and efficacy can vary.

- Prescription status: It’s not available as a prescription medication in most countries.

- Clinical trials: There might be ongoing or planned clinical trials investigating its use in humans, but these would be limited to research participants.

- Potential future development: Given the promising results in animal studies, pharmaceutical companies might be interested in developing this as a treatment, but that process would take years.

- Alternative options: Patients interested in this approach should consult their healthcare providers. They might recommend other available treatments that target similar mechanisms, such as 5-HTP supplements or SSRIs, which are more readily accessible.

- Safety considerations: The safety profile in humans, especially for long-term use, has not been thoroughly established.

Glycine-tryptophan dipeptide Safety Profile

- There’s no direct evidence suggesting it would be unsafe in humans.

- The study used it in animal models without reporting significant adverse effects.

- Glycine and tryptophan are both naturally occurring amino acids that are generally well-tolerated.

Administration route:

- The research suggests it does not require injection.

- In the animal studies, it was administered orally, likely as a dietary supplement.

- The whole point of using the dipeptide form is to improve oral absorption, bypassing the impaired amino acid transporters in the intestine.

Lack of long-term human studies:

- While there’s no evidence of harm, there’s also limited data on long-term use in humans specifically for this purpose.

- Most safety data would come from general knowledge about these amino acids rather than this specific formulation.

Regulatory status:

- It’s not classified as a drug, which means it hasn’t undergone the rigorous safety testing required for pharmaceuticals.

- However, this also means it’s likely to be considered a dietary supplement, which generally have good safety profiles.

Potential interactions:

- As with any supplement affecting amino acid metabolism, there could be interactions with medications or other health conditions, but these are theoretical without specific studies.

Natural components:

- Both glycine and tryptophan are found in the diet, which suggests a basic level of safety, though the dipeptide form might have different properties.

In summary, while there’s no clear evidence of safety concerns, the lack of extensive human studies means caution is warranted. It would likely be taken orally, not injected. As always, anyone considering such a supplement should consult with a healthcare provider, especially given the complex nature of long COVID and potential interactions with other treatments.

Potential Paths to Addressing the Root Cause of Intestinal Viral Inflammation

Based on the information provided and our understanding of viral inflammation in long COVID, here are some possible solutions to address the underlying viral inflammation:

Antiviral treatments:

- Developing targeted antivirals that can eliminate persistent viral reservoirs, especially in the gastrointestinal tract.

- Exploring the use of existing antivirals that might be effective against SARS-CoV-2 remnants.

Anti-inflammatory interventions:

- Using anti-inflammatory medications to reduce the chronic inflammation caused by viral persistence.

- Investigating the potential of corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory drugs for long-term use in PASC patients.

Interferon modulation:

- Since type I interferons are implicated in serotonin reduction, developing therapies that can normalize interferon levels without compromising immune function.

Gut microbiome interventions:

- Using probiotics or other microbiome-modulating therapies to restore gut health and potentially reduce gastrointestinal inflammation.

Dietary interventions:

- Implementing anti-inflammatory diets to support overall reduction in systemic inflammation.

Targeting specific inflammatory pathways:

- Developing drugs that inhibit specific inflammatory cytokines or signaling pathways involved in long COVID.

Immune system reset therapies:

- Exploring treatments that can “reset” the immune system to stop the cycle of chronic inflammation.

Platelet-targeted therapies:

- Developing treatments to address platelet dysfunction and reduce hypercoagulability.

Vagus nerve stimulation:

- Using this approach not only for its effects on serotonin signaling but also for its potential anti-inflammatory properties.

It’s important to note that while these are potential solutions, many would require significant research and clinical trials before they could be implemented as treatments for long COVID patients. The complex nature of the condition means that a combination of approaches may be necessary for effective treatment.

References

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867423010346

Leave a Reply